Thanks to the Financial Press, the Odds of a Fed Policy Mistake have Gone Up Dramatically

- CitizenAnalyst

- Sep 6, 2022

- 13 min read

During his press conference following the Fed's meeting on July 26-27, Chair Powell stated that "as the stance of monetary policy tightens further, it likely will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases while we assess how our cumulative policy adjustments are affecting the economy and inflation." About a half hour or so earlier, the FOMC press release had begun with the statement "recent indicators of spending and production have softened." The Fed's seeming acknowledgment that its rate increases were slowing the economy, and its admission that the 75 bps rate increases it had undertaken in June and July were probably not going to be necessary indefinitely, drove a rally in the stock market. The key inflection point can be traced almost to the second when Powell uttered the words highlighted above about the pace of future rate increases. The market was concluding that "peak Fed" was likely behind us, and that slower, more normal increases from here were more likely. Importantly, however, it was not concluding that the Fed was done hiking. Instead, since the huge rate increases to this point had not put us into a deep recession, the market was starting to sniff out the end of the hikes, and consequently, the bottom in the economy. If you look back in history, the stock market does not bottom when the economy bottoms, but instead, almost always before it. It usually tends to bottom when the Fed "pivots," either because it sees the end of the hikes on the horizon, or because the Fed has actively told them its done hiking. Key examples of this were August 1982 (when Volcker more clearly indicated he was backing off), January 1995 (when the market concluded Greenspan would likely be done hiking by mid-year 1995), and in December 2018 (when Chair Powell highlighted "Cross-Currents" in the economy had developed and indicated two rate hikes were likely to be appropriate in 2019 instead of three).

Even before the July Fed meeting, however, evidence was mounting that inflation was in fact starting to slow. Many investors (myself included), had been head faked a few months earlier that "peak inflation" happened in March, only to see the ripple effects of the Russia / Ukraine War reverberate through the economy and tear that thesis to shreds. By June and July, however, there was significant evidence that the peak inflation thesis was actually playing out, the most notable of which was the significant decline in spot transportation rates, particularly spot trucking and ocean freight rates. Transportation inflation had, after all, along with labor, been a key driving source of aggregate inflation over the previous year. And though it wasn't unanimous or ubiquitous quite yet, company commentary about both labor markets loosening and supply chains normalizing were becoming increasingly common.

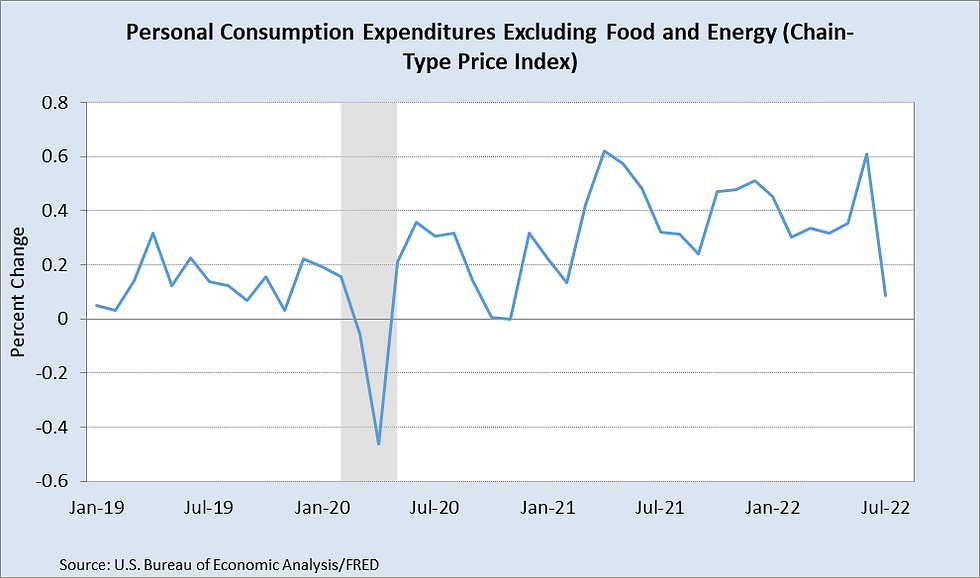

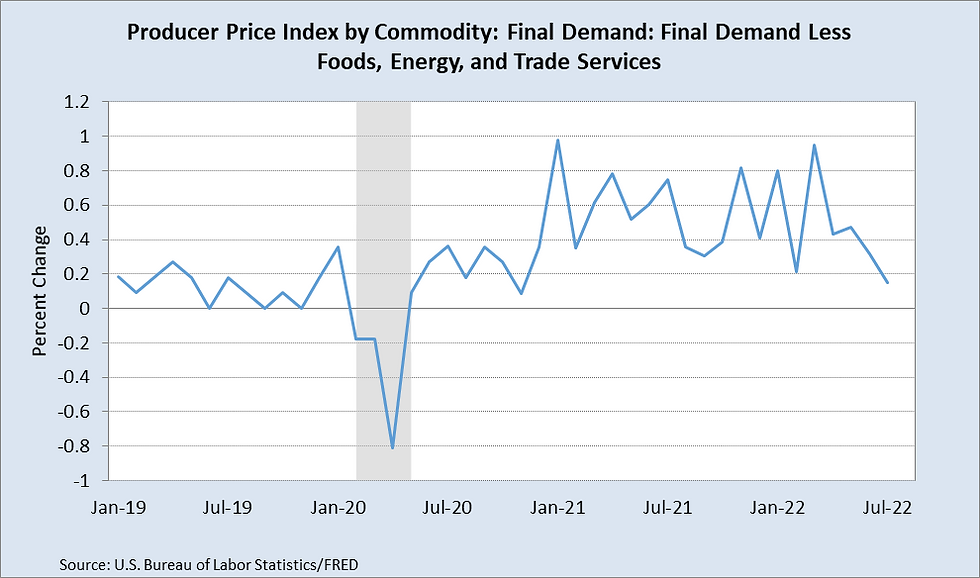

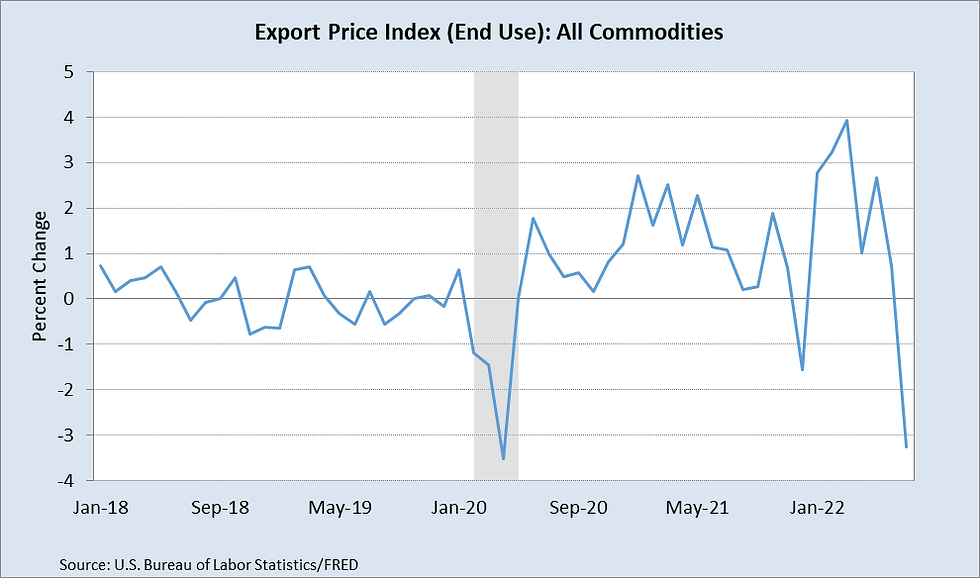

Over the next month or so, "macro" inflationary indicators continued to come in favorably, following the more favorable "micro" commentary from companies during 2Q earnings season. The most notable of this was the July CPI report on August 10th, where core inflation surprised to the downside, increasing at a seasonally-adjusted rate of 0.3% month-over-month. This implied an annualized rate of core inflation of 3.6%, still above the Fed's 2% target, but a marked improvement towards that level from May and June's 0.6% and 0.7% monthly increases (which imply annualized rates of 7.2% and 8.4% respectively). The next two days, July PPI and Import / Export price changes also showed very promising improvement and added fuel to the rally in the stock market that the Fed's actions taken to date were working, and that the end of hikes were not imminent, but in sight.

Importantly, however, as noted above, the stock and bond markets were not concluding that the Fed was going to stop hiking immediately. They instead were concluding that fewer rate increases from here were going to be needed to get inflation back to appropriate levels (which the Fed has clearly stated is an annualized rate of 2%). As the charts below indicate, Fed Futures markets indicated that the Fed was still likely to keep hiking until it reached a Fed Funds rate of about 3.7% in February of 2023. But, and this is crucial, the market had also continued to conclude that a recession was very likely between now and then, if we weren't in the middle of one already. The best evidence for this of course was the steep inversion in the Treasury Yield Curve, most notably between 2 and 10 year government bonds. Though not infallible, the 10-2 Treasury spread is about as reliable of a recession indicator as it gets.

To summarize then, the market had concluded that through the middle of August, the Fed's actions were working to slow the economy, and to slow inflation. But, it continued to conclude that the Fed was going to raise rates to about 3.7% (compared to the 2.25-2.5% range as of the July meeting), and that this was going to cause a recession. It was for this reason, and not because the market thought the Fed would blink on inflation, that market participants had priced in cuts for the July 2023 FOMC meeting. Said differently, the market thought the Fed would continue to hike through February of 2023, this would cause a recession, and that recession would fix our inflation problem, and it would allow the Fed to start cutting rates again back towards neutral by the middle of next year.

Now, following the July Fed meeting and the stock market rally in early August, the Financial Press got a hold of the narrative that the Fed Futures were pricing in cuts to the Federal Funds rate in 2023, and naturally conflated the pending cuts with the rise in equities. There is a long list of articles demonstrating this narrative's growing significance during this period, but a good example of this came from the article "Wall Street Bets the Fed Is Bluffing in High-Stakes Inflation Game," published on August 18th (https://www.wsj.com/articles/in-high-stakes-inflation-game-wall-street-bets-the-fed-is-bluffing-11660830685?tpl=centralbanking). This article puts forth the notion that the financial markets think the Fed is bluffing on inflation and that it will back off before the job is done, and that is why markets are pricing in rate cuts in 2023. This is completely wrong. If this was the case, then inflation breakevens--the difference between nominal Treasury bonds and inflation adjusted Treasury Bonds, commonly known as TIPS (Treasury Inflation Adjusted Securities)--would have started to move higher in a big way. But throughout this period, inflation forecasts from the market did no such thing: they ticked up modestly at the time of the Fed's July meeting, but then were essentially flat since then until very recently (when they've again ticked back down). And importantly, throughout this period they remained considerably below levels from earlier this year, as the chart below shows.

As noted above, the article cited above and many others have created a narrative that the Fed is going to blink on inflation before it finishes the job. Because of the nature of inflation and its sensitivities to expectations, this rightly alarmed the Fed. It shouldn't surprise us then, that over the last 2-3 weeks, almost every Fed official has had to come out and squash this narrative. Some examples:

On Tuesday August 2nd, San Francisco President Mary Daly in an interview with CNBC anchor John Fortt on LinkedIn laughed at the suggestion of rate cuts in 2023, and then stated rate cuts "would not be my modal outlook...my modal outlook, or the outlook I think is most likely, is really that we raise interest rates and then we hold them there for a while at whatever level we think is appropriate." https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/feds-daly-work-inflation-nowhere-near-almost-done-2022-08-02/. Then on August 18th, Daly reiterated this by saying "I really think of the raise-and-hold strategy as one that has historically paid off for us...we want to not to have this idea that we will have this large, hump-shaped rate path where we will ratchet up really rapidly this year and then cut aggressively next year." https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-18/fed-may-need-to-raise-rates-above-3-to-cut-inflation-daly-says.

On August 18th, St. Louis Fed President Bullard reiterated his claim that he expects elevated inflation "to prove more persistent than what many parts of Wall Street think." The WSJ also quotes Bullard as saying "that market speculation over rate cuts is 'definitely premature.'" https://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-bullard-leans-toward-favoring-0-75-percentage-point-september-rate-rise-11660842768.

Then on August 30th, Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic remarked that "Still, even as certain inflationary pressures appear to be ebbing, we know we have a fight ahead...while the July consumer price index report represented a reprieve in the pace of price increases, it also makes clear that price pressures remain stubbornly widespread and not confined to a few items...What economists have come to call stop-and-go monetary policy—tightening in the face of rising inflation but then reversing course abruptly when unemployment rises—arguably helped to fuel inflation during the late 1960s and 1970s. Partly as a result, elevated inflation took root and policymakers ripped it out of the economy only after a pair of recessions in the early 1980s." Bostic's remarks do support the notion, however, that over-hiking and then being forced to cut because they're doing too much damage doesn't do anyone any good either. Nonetheless, Bostic reiterated that "even though it will take time to see the full effect of the policy adjustments we have made to date, I don't think we are done tightening. Inflation remains too high, and our policy stance will need to move into restrictive territory if inflation is to come down expeditiously. That said, incoming data—if they clearly show that inflation has begun slowing—might give us reason to dial back from the hikes of 75 basis points that the Committee implemented in recent meetings. We will have to see how those data come in." https://www.atlantafed.org/about/atlantafed/officers/executive_office/bostic-raphael

On August 31st, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester stated in her speech that she did not see rate hikes in 2023. She stated: "My current view is that it will be necessary to move the fed funds rate up to somewhat above 4 percent by early next year and hold it there; I do not anticipate the Fed cutting the fed funds rate target next year. But let me emphasize that this is based on my current reading of the economy and outlook. While it is clear that the fed funds rate needs to move up from its current level, the size of rate increases at any particular FOMC meeting and the peak fed funds rate will depend on the inflation outlook, which depends on the assessment of how rapidly aggregate demand and supply are coming back into better balance and price pressures are being reduced."

The exclamation mark on this narrative recapture from the Fed of course was Chair Powell's speech at the Jackson Hole conference on August 26th, where he emphatically said they were going to do whatever it takes to get inflation back down to 2%. Key comments from Powell's speech included:

"While the lower inflation readings for July are welcome, a single month's improvement falls far short of what the Committee will need to see before we are confident that inflation is moving down."

"In current circumstances, with inflation running far above 2 percent and the labor market extremely tight, estimates of longer-run neutral are not a place to stop or pause."

"Restoring price stability will likely require maintaining a restrictive policy stance for some time. The historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy. Committee participants' most recent individual projections from the June SEP showed the median federal funds rate running slightly below 4 percent through the end of 2023. Participants will update their projections at the September meeting."

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20220826a.htm.

Then last week in an interview with the WSJ's Nick Timiraos and New York Fed President John Williams (https://www.wsj.com/articles/transcript-wsj-q-a-with-new-york-fed-president-john-williams-11661885347), the following exchange took place:

Williams: I do feel that, you know, next year, you know, because of the lags in monetary policy, because some of the highest of inflation, I think, are going to be somewhat persistent, we’re going to need to have restrictive policy for some time. This is not something that we’re going to do for a very short period of time and then, you know, change course. It’s really more about getting policy to the right place to get inflation down and keeping it in a position that helps make sure that in the next few years not only are we moving to 2 percent, but we achieve our 2 percent inflation goal on a sustained basis

WSJ's Timiraos: So people ask about the Fed’s reaction function, which really means how the Fed reacts to different incoming data. And this year the focus has been on the speed of rate increases. You’re talking about sort of a time dimension, getting to a place and then holding there. The market has been pricing in rate cuts. Are you saying that you don’t think that’s a realistic scenario at this point? Rate cuts, specifically happening next year?

Williams: Well, I think currently the [market is] pricing in about one rate cut next year right now. So and that’s going to depend on where things are. But honestly, from my perspective right now, I see us seeing needing to kind of hold this – you know, a policy stance of pushing inflation down. Bringing demand and supply into alignment is going to take longer than – you know, will continue through next year. So that’s my view right now. And I think it’s – you know, based on what I’m seeing in the inflation data, what I’m seeing in the economy, it’s going to take some time before I would expect to see any adjustments of rates downward.

The major disconnect here of course is the question of a recession. Fed officials will rarely admit that they think they're going to cause a recession, but its not unprecedented that they do so. Volcker routinely admitted when he thought the economy was in a recession (which it was for a lot of his tenure). To this point, however, current Fed officials unanimously do not seem to think that their policy actions are going to cause a recession, but rather only "some pain." They've given some indication between the lines that they may end up causing a recession, but they do seem to pretty convincingly believe that if they do, it won't be a bad one. Thus, a "soft" or "soft-ish" landing is by no means impossible in their eyes, and that outcome does not seem to be merely political window dressing. But because the market thinks the Fed is going to cause a recession, and the Fed themselves does not, there is a disconnect between the root cause of why markets were pricing in rate cuts in 2023. Amazingly, the WSJ article cited above does not mention the word recession once, nor do most other articles discussing this topic. Reporters repeatedly continue to ask Fed officials about rate cuts in 2023, but never add the all important context of recession, instead trying to focus on how the market has gotten things wrong and is out of sync with what the Fed is saying and doing. In the WSJ interview with New York Fed President John Williams cited above, Nick Timiraos did this very thing yet again.

Weary of losing control of the anchored inflation expectations they've been working so long to control, Fed officials have come out in full force to crush this narrative, as highlighted above. Of course, if the Fed doesn't think they're going to cause a recession, why would they cut rates in 2023? If they don't think they're going to cause a recession, then of course they're going to say they aren't going to cut. Without the context of a recession, however, Fed officials politically have no choice but to respond hawkishly. The problem is that the full context of the disconnect between markets and the Fed is never provided, so it confuses people.

Now, why is this a problem and why should we care? Because if this kind of false narrative gets too much press, it may affect inflationary psychology, and as Chair Powell said in his Jackson Hole speech, "if the public expects that inflation will remain low and stable over time, then, absent major shocks, it likely will. Unfortunately, the same is true of expectations of high and volatile inflation." A false narrative like this therefore makes the Fed's job harder than it otherwise needs to be, and may force them to hike rates more than they otherwise would, all other things being equal. Everyone wants the inflation problem fixed, but no one wants more pain than we absolutely need to to fix it. But this is the position the press has put the Fed, and the repeated commentary from Fed officials both before and after the Jackson Hole speech has spooked the markets into the belief that the Fed now is going to over-hike just as inflation is coming under control. The very morning of the Jackson Hole speech last Friday, we got a Core PCE reading for July of 0.1% and more encouraging data from the University of Michigan on inflation expectations (1 year inflation expectations hit a 9 month low at 4.8% and 5 year expectations remained subdued at 2.9%). July Core PCE's 0.1% seasonally-adjusted increase annualizes to a core inflation rate of 1.2%, or well below the 2% target the Fed is looking for. To be sure, it's one month, and its certainly possible this is some version of the "head fake" we saw in March, but that does seem increasingly unlikely now. Not once did the seasonally adjusted monthly Core PCE come in at 0.1% during Volcker's tenure, and outside of brief periods in late 1971 and late 1972, core PCE did not come in at 0.1% in any month from 1967 through May 1983, the entire period of the Great Inflation. That is very encouraging.

CPI, PPI, Import Export prices, PCE, University of Michigan surveys, NY Fed Inflation Expectation Surveys and other Regional Fed surveys all point in the same direction, and that is that inflation is getting better, and it may be doing so much more quickly than we realize. We may already be at a run-rate level of 2%. Because of the erroneous narrative put forth by the press that the Fed is going to "blink," however, the Fed has had to basically ignore the improvements made to date and sound as hawkish as possible so as not to confuse people. On 8/31, Cleveland Fed Governor Mester, who votes on the Committee somewhat amazingly quoted the year-over-year inflation figures for July's PCE of 6.4% rather than highlighting the monthly increase of 0.1%, and she also chose to look at Mean Trimmed PCE on a year-over-year basis as well (https://www.clevelandfed.org/en/newsroom-and-events/speeches/sp-20220831-returning-to-price-stability.aspx). This is a bit like looking at last-twelve-months (LTM) EBITDA when the most recent quarter's EBITDA looks meaningfully better than the 4th most recent quarter. Said differently, looking at inflation on a year-over-year basis incorporates a lot of inflation that already happened 6-12 months ago. Rather than emphasizing the most recent seasonally-adjusted monthly changes, which more accurately reflect current inflationary momentum, Fed officials are deliberately choosing to view the inflation glass as half-empty to manage expectations accordingly. This drum-beating over the last two weeks has perhaps not surprisingly driven expectations for Fed rates back up to the point where there's now almost no cuts priced in all the way through July 2023, but had the press not created this false narrative, they probably wouldn't have needed to do this. Given the current momentum of inflation, where inflation may already be back down to our 2% target with only a "neutral" Fed Funds rate, were the Fed to follow through on this new expected path of rates, it would likely cause a more severe recession than necessary. This is what market participants call "a policy mistake," and thanks to the financial press, the odds of such a policy mistake have now gone up dramatically.

Comments