Beginning with the July Fed Meeting, Fed officials admitted the economy was slowing. This was likely the major driver behind Chair Powell’s comment in the July meeting press conference about it eventually becoming necessary to slow the pace of rate hikes to more “normal” levels (so more like 25 bps a meeting instead of our current 75 bps). But while Fed officials have done their best to sound as Hawkish as possible lately (something I believe was caused by a distorted narrative in the press about markets not believing the Fed has the audacity to finish the job; here’s another example on that from this week: https://www.cnbc.com/video/2022/09/07/fed-vice-chair-brainard-we-are-in-this-for-as-long-as-it-takes-to-get-inflation-down.html), one thing that has been consistent since even before July is the Fed’s reliance on a strong labor market as a barometer of the strength of the economy.

In normal times, this probably makes sense. Since 1950, the correlation between real GDP and non-farm employment in the US is 98%, with an R-squared of 95%. This makes sense right? The economy is generally a function of the number of workers, and the productivity (or output) of those workers. But there’s a major difference between the economy over the last two years and “normal times,” which is that we were paying people whether they were working or not for a significant part of that period. Thus, as stimulus has faded and unemployment benefits have expired, many of those people have either finally run out of savings, or felt comfortable enough to come back to work (or some combination of both). Employment is usually a lagging indicator in economics, but in the circumstances of the last few years, it’s a major lagging indicator. Thus, using the influx of labor and job growth in 2022 as a barometer for strength in the economy is likely to be overstating the case. And given the Fed appears to be using the labor market as the key source of economic strength, it feels increasingly likely like a policy mistake (read: recession) is on the way.

To explain in a bit more detail what I mean, let me paint a theoretical picture of the progression of the economy from the start of the pandemic until today. Like most theories, this one certainly isn’t 100% correct, but it seems pretty reasonable that a lot of this is directionally true. In March of 2020, in response to a virus that at that time we knew little about, a significant chunk of workers got laid off, and many people were also put on some form of temporary leave. The government responded with massive stimulus packages in March of 2020 ($2.2T) , December of 2020 ($900B), and then again in March of 2021 ($1.9T), which combined to total roughly 23% of US GDP of $21.7T as of 4Q19. Additionally, though it varied by state, supplemental unemployment benefits were put in place at both the state and federal levels, and to varying degrees lasted all the way through fall of 2021.

The timing of the stimulus checks versus the timing of the expiration of the unemployment benefits is the key part of the story here. Notice in the charts below how GDP and employment have trended since 4Q19, the last quarter before the pandemic hit. At first GDP led employment down, but then employment sunk way faster than GDP. After that, GDP bounced back much quicker than employment, with employment just now getting back to pre-COVID levels in July 2022, while GDP was already above pre-COVID levels by 2Q21.

This chart shows the path more clearly, with employment and real GDP anchored to their 4Q19 levels. You can clearly see that GDP fell faster at first, but then bounced back much faster than employment, and even exceeded pre-COVID levels by 2Q21.

What was happening underneath the surface was that businesses were learning how to do more with less, as the demand in the economy was quickly returning to levels that it otherwise only would have had a significantly greater number of people been working. Said differently, the stimulus and unemployment benefits we provided for so long did what they were supposed to do, and kept demand at elevated levels while we figured out how to deal with COVID. But the practical implications of this was that with real demand higher than it was pre-COVID by 2Q21 (by about 1%), but employment still about 4% below at the same junction, workers had to essentially become 5% more productive than they were before COVID in order to make this work without price inflation becoming an issue. But with so many workers changing jobs and so much temporary labor being used, it’s becoming increasingly clear that this simply didn’t happen. Despite the country’s issues with worker productivity over the last couple decades (which we’ll save for another day), many investors, myself included, did not think a 5% improvement in worker productivity was that big of a stretch considering all the new tech and software that was implemented, not to mention the fact that this was a once in a lifetime chance for many businesses to learn how to operate with meaningfully less revenue than you had before. After all, sometimes you don’t know what you can do with the resources you have until others are taken away.

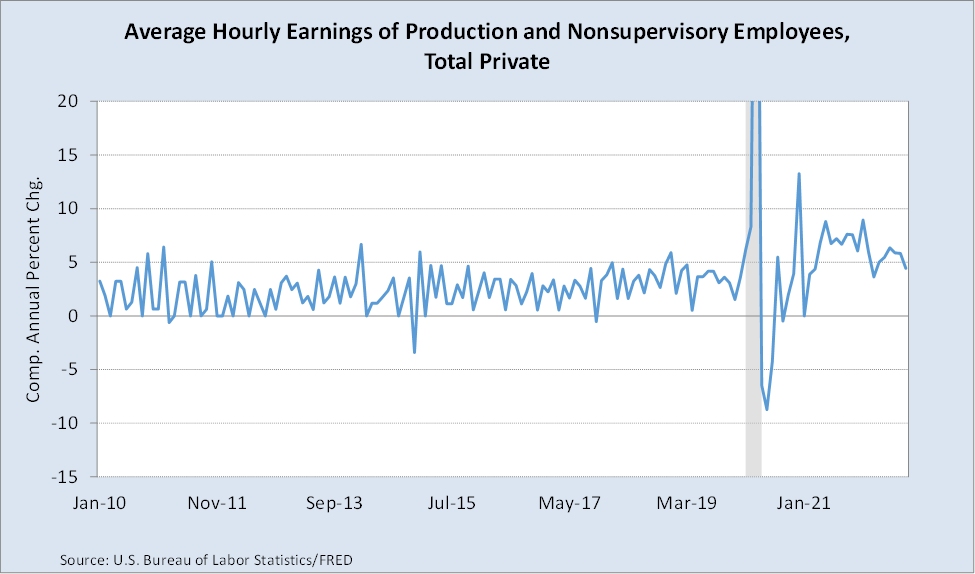

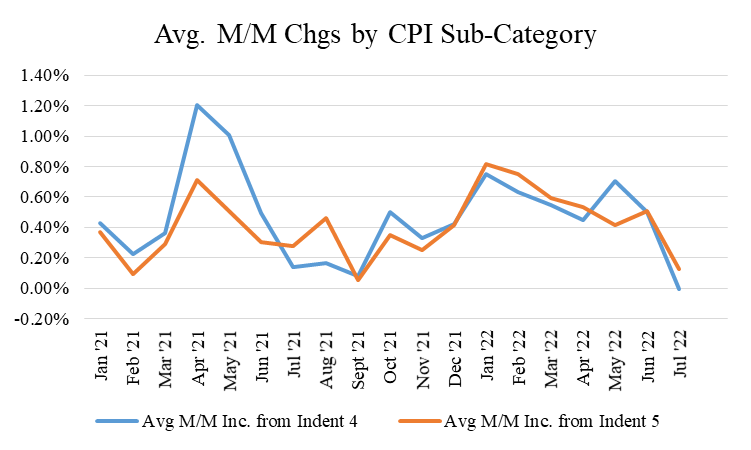

But with so much worker turnover, however, it quickly became clear that workforce productivity did not improve as much as we needed to avoid significant inflation. Since the demand was still there despite employment still being depressed, businesses decided to pay up to get whatever employees they could. Because many businesses were doing that at once, however, this created massive wage inflation as everyone competed for the same employees. This is only now starting to cool. The August jobs report showed annualized wage inflation of 3.6% (for all private employees) and 4.8% (for production and nonsupervisory workers), not far above where wage growth was pre-COVID. Many observers, just as they do with inflation, continue to call out the year-over-year figures, but this gives too much weight on wage increases that took place 6-12 months ago when the labor market was in a much different place. Said differently, looking at year-over-year changes do not give you as accurate a picture of current inflationary momentum. Looking at the most recent month, annualized, does. The two charts below show this more clearly.

Getting back to our narrative, because the workers many firms did hire over the last 12-18 months were newer and didn’t know how to do those jobs as well as more seasoned employees, businesses couldn’t meet the increased demand without more employees. And because getting more employees just wasn’t an option because workers remained on the sidelines, businesses raised prices, either to deter demand, to capitalize on demand, or to pass through the higher labor costs they were seeing. This dynamic is very likely to be the general culprit of our current inflationary predicament today. Now throw in a war in Europe, and a Zero COVID policy in China (which exacerbated all of the dynamics I described above in that country, except multiple times now), and you can start to understand the mess we’ve put ourselves in.

It's been my view that most of our issues have been caused by “supply” bottlenecks rather than too much demand. This was also the market’s view, and the Fed’s view, for most of 2021. But eventually, the Fed (probably rightly) grew fatigued with waiting for the labor force to normalize and for supply chain issues to resolve themselves, and started to aggressively raise rates this year to bring demand back down in line with supply. More than one or the other, it was the combination of the two—supply shocks and demand surges—and even more importantly, the incongruent timing of the two, that has produced the issues we face today.

But now, with a substantial number of workers coming back into the workforce and taking jobs again, and demand starting to cool at the same time, supply and demand is increasingly coming back into balance, and quite quickly in some cases. In the second quarter, real GDP per worker was now only 3% above where it was prior to COVID. Though work-from-home and all the people with new jobs are still likely settling in (Sysco, the restaurant food distributor, amazingly said that roughly half of its supply chain workforce had been on the job for one year or less as of 2Q22), the latest inflation data in both wages (highlighted above) and prices (see below), suggests that we’re coming into balance quite quickly, even with short-term interest rates only at “neutral.” We may actually already be at 2% inflation (July's core CPI increase of 0.3% implies annualized inflation of 3.6%, while July's core PCE increase of 0.1% implies annualized inflation of only 1.2%), though that will be confirmed or proven wrong in coming weeks and months.

The Fed’s focus on the labor market also appears to be misstating the case in another way as well. If you believe that the supply issues are mostly caused by not having enough workers, then job growth itself is not necessarily inflationary. Wage growth to a certain extent is inflationary, but job growth itself is not. In fact, job growth itself is probably deflationary. But as recently as Thursday, St. Louis President James Bullard again put forth the view--which to be fair seems to be held by most Fed officials--that a big jobs number is probably inflationary, stating “I was leaning toward 75 and the (August) jobs report was reasonably good last Friday… So I am leaning more strongly toward 75 at this point.” The Fed therefore seems to be mistakenly viewing the labor market as the best indicator for overall strength in the economy, and as the best indicator for inflation. Somewhat amazingly, Bullard also seemed to suggest he didn’t care what next week’s CPI showed, and is going to vote for 75 bps anyways. He stated, “I wouldn’t let one data point sort of dictate what we are going to do at this meeting.” (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-09/fed-s-bullard-leans-more-strongly-to-third-75-basis-point-hike). This is particularly concerning given July's CPI, PPI, Import / Export price data, and PCE inflation figures all pointed in the direction of solid improvement. Thus, August’s CPI is no longer “one data point.” More generally though, this is concerning because it does not show an attitude of “data dependence.”

I’ve spoken elsewhere (mainly here: https://www.citizenanalyst.com/post/thanks-to-the-financial-press-the-odds-of-a-fed-policy-mistake-have-gone-up-dramatically) about the Fed quickly moving into over-hiking and policy-mistake territory over the last month. My view was they were responding to a false narrative in the press about them not having the courage to finish the job on getting inflation down, and they’ve responded aggressively to the contrary over the last several weeks. But with supply and demand quickly coming into balance (as evidenced by the latest wage and price inflation data, not to mention a litany of company commentary about supply chains improving), Fed officials’ insistence even as recently as the last two days that they’re not going to stop hiking until something like 4% is reached suggests they’re going to overdo it. Chicago Fed President Evans commentary about hiking to 4% and even being very reluctant to pause at 3.5% (a full 100 bps above where we are today) is a good example of this (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-08/fed-s-evans-sees-another-jumbo-rate-hike-on-table-in-september?srnd=economics-vp).

The fact that the economy has come much closer into balance with rates only at “neutral” (~2.25-2.5%) suggests two things. First, that Fed commentary about future rate hikes, or said differently, its forward guidance, has pulled forward the impact of future rate hikes faster than they have in the past. By openly saying they’re going to hike to 3.7-4% (the levels suggested by the Fed’s most recent SEP), the market has priced this into many of the key interest rates that many of us borrow on today already (with mortgage rates being a good example of this). In the past, the Fed didn’t take this approach, and so it took longer for Fed rate hikes to be felt in the economy. This time is a bit different in that regard, such that in practice, we may already be well above “neutral” in the real economy. Put differently, the lag to monetary policy has probably shortened considerably because of how publicly vocal the Fed has been during this hiking cycle. Second, it suggests that lower worker productivity may mean "neutral" Fed Funds is actually lower than we think, and that the economy has slowed as much as it has because we may actually already be in restrictive policy territory today.

The problem is that while the Fed's forward guidance pulls forward some of the impact of future rate hikes, it does not pull forward all of it. Notably, while treasury, corporate and mortgage rates all respond to this Fed commentary because they are market rates, banks tend to raise their rates in conjunction with actual changes in short-term Fed funds rates. Bank rates are a better barometer of borrowing costs for small and medium sized businesses, so it affects them later. Thus, future rate hikes are almost certainly not yet fully baked into the economy.

Much discussion has taken place about whether we are currently in a recession or not. While GDP may be understated for a variety of reasons, it’s pretty clear that real growth in the economy is barely positive right now, if its positive at all. We may not be in a recession despite the two consecutive quarters of negative GDP, but at best, we’re very much flirting with one, and significant further Fed hikes like the kind that are being talked about by Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester and Chicago Fed President Charles Evans to 4% by year end could potentially do significant damage to economy, and potentially unnecessarily so.

Now, let me be clear about one thing. I'm not advocating for the Fed to stop hiking today. They have done an admirable job so far of reining in demand with their rhetoric by letting the market do their bidding for them. My fear though is that the Fed has boxed themselves into a certain path of rate hikes and no longer has the wiggle-room to be “data dependent.” It’s not just the path itself either, but how fast we travel down that path that matters. Going slower is not accommodative, yet we seem to have quickly become sensitized that any rate increases less than 75 bps somehow is accommodative. Instead of slowing things down from here, the Fed is putting high numerical targets out there (with the nice round number of 4% being most frequently cited these days) to combat this narrative in the press that they’re wimping out on the inflation fight. This rhetoric, and the "soft" Fed Funds rate targeting that's come with it, will make it increasingly difficult optically and politically for the Fed to pivot if in fact inflation data continues to follow the progress we saw in July. All of this rhetoric has been digested in markets such that 75 bps at the September meeting in two weeks is almost a sure bet (https://www.cmegroup.com/trading/interest-rates/countdown-to-fomc.html).

It is hard to reconcile how Powell could feel compelled to prep the market for slowing the size of increases at the July Fed meeting, then have inflation data for the next month almost uniformly get significantly better, while data for the rest of the economy remains tepid at best, only to have the Fed again come out and say another enormous increase is warranted again in September. That is not being data dependent. Instead, it feels like an institution responding to a narrative that they don’t have the gumption to finish the job. That is how policy mistakes happen.

Now, despite my growing fears about the Fed abandoning data dependency and unnecessarily boxing themselves in, there do appear to be some silver linings in recent Fed commentary. First, the Fed does appear to be leaving some breadcrumbs to allow a close observer to think they won’t overdo it. Despite the somber, hawkish tone of his Jackson Hole speech, even Powell still decided to leave the line about slowing the pace of future rate increases from his July press conference in the Jackson Hole speech. Additionally, Lael Brainard, in her speech this week on 9/7, signaled that it may only require “several” more months of inflation improvement of the kind we saw in July to allow the Fed to slow the pace of increases (https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20220907a.htm). Additionally, her comments that “at some point in the tightening cycle, the risks will become more two-sided” were encouraging, and echoed what Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said on 8/30 as well (“we must weigh the risk of our policy action from both sides—moving either too aggressively or too timidly has downsides” see: https://www.atlantafed.org/about/atlantafed/officers/executive_office/bostic-raphael). And for all her hawkishness, even Loretta Mester stated in her speech from 8/31 that her views were “as of now” and subject to change. Of course, one thing that also needs to be recognized in this context is that it will be difficult for the Fed to leave interest rates “higher for longer” if they over-hike, which is also another reason why they have an incentive to not keep front-loading these hikes in such a large way, and instead to reduce the pace back down to a more “normal” 25 bps soon. But this requires the Fed to get the press to understand that doing “only” 50 bps (or eventually, 25 bps) is not waving the white flag on inflation. Given the improvements we seem to be seeing on inflation, changing this narrative in the press may actually be their toughest task now.

To summarize, my issue is not so much with the Fed hiking in principle. I’m certainly not saying they should stop hiking period right this second. They probably do still need to continue to hike. What I am concerned about is that the Fed seems to have abandoned their emphasis on data dependency to try and look tough by rushing big rate hikes, just as inflation appears to be cooling, and supply and demand is coming into better balance. So now, they’ve boxed themselves in even further, which is problematic considering that we don’t really know what “neutral” or “restrictive” policy is in the post-pandemic economy. What if we’re already at restrictive policy because working-from-home and everyone switching jobs has sapped worker productivity even further going forward? By rushing things to look tough though, the Fed is removing a lot of their optionality to figure these things out, and instead, dramatically increasing the odds of a policy mistake, and unnecessary economic pain.

Comments